How Scenic Hudson “Segmented” the Fjord Trail and Avoided Strict Environmental Review

In December 2022, Scenic Hudson got environmental review approval to build a $59.1 million pedestrian bridge over the Metro North railroad tracks at Breakneck Ridge. The bridge, together with State Route 9D improvements there, represents the first construction phase of the Fjord Trail, the controversial 7.5-mile planned riverfront walkway from Cold Spring to Beacon.

Critics have said that the bridge decision prejudiced the overall Fjord Trail environmental review process – once you build the big, expensive bridge, the rest of the Fjord Trail inevitably will be approved, regardless of the wisdom of doing so, or the environmental consequences. After all, no public official wishes to be associated with a “Bridge to Nowhere.”

Scenic Hudson needed approval under the State Environmental Quality Review Act, or SEQRA. Normally, approval would be for the entire Fjord Trail, considered as a whole. But Scenic Hudson had a different strategy, called “segmentation.” It wanted to divide up the Fjord Trail into segments, and seek separate environmental approvals for each segment. The first segment would be the “Breakneck Connector and Bridge,” located at the very middle of the overall trail.

With limited exceptions, however, “segmentation” is illegal under SEQRA.

This report examines how Scenic Hudson got the Breakneck segment approval.1 We focus in particular on the Breakneck bridge – should Scenic Hudson have been allowed to build that, before the rest of the Fjord Trail was approved? Doesn’t building the bridge put the cart before the horse, with prejudicial effects? This report considers:

Why segmentation is contrary to the intent of SEQRA;

Why developers try to segment their projects;

The questionable arguments that Scenic Hudson made for segmentation;

Whether the State agency that approved the segmentation, the Parks department,2 was sufficiently objective to take the requisite “hard look” at Scenic Hudson’s application; and

Scenic Hudson’s failure to discuss the project’s likely effect on the 13 endangered or rare species that may be found in the Breakneck area.

CLICK BELOW TO DOWNLOAD A PDF FILE OF THIS ENTIRE REPORT:

A BRIEF HISTORY OF THE FJORD TRAIL

The concept of a trail of some kind to connect Cold Spring and Beacon has been debated for decades.

The idea got kick-started in 2007, when the Town of Philipstown proposed the “Hudson Fjord Hike/Bike Trail.” The plan had two elements: long-desired traffic and parking improvements along Route 9D north of Breakneck Ridge, plus a two-mile bicycle and pedestrian path.3 The path, along Route 9D, would “connect” hikers to six state park trailheads.4

The 2007 plan was estimated to cost between $2.8 million and $3.3 million. But with every fresh iteration, the Fjord Trail has gotten more ambitious and expensive.

In 2012, Scenic Hudson agreed to coordinate the project. A handful of non-profit groups and public agencies signed on. Scenic Hudson’s 2015 Master Plan proposed a longer, seven-mile, version of the Fjord Trail, from Cold Spring to Beacon. The route would go inland along Fair Street in Cold Spring; then on the riverfront from Little Stony Point to Breakneck; then to Beacon. The 2015 Master Plan stalled for lack of money.5

In 2017, Garrison resident Christopher C. Davis took over. Davis thought the existing plans were “a little bit soulless, because they didn’t connect to the landscape.”6 Davis, who runs a family-owned mutual fund company, paid for the 2020 Master Plan.7 Scenic Hudson hired new landscape architects, designers, engineers, and other consultants. The re-imagined Fjord Trail envisioned a “world-class” “linear park of exemplary design.” The route along Fair Street was abandoned. Instead, the trail would begin at Dockside Park in Cold Spring and follow the riverfront for two miles to Breakneck Ridge, then go inland to Beacon. The two-mile riverfront stretch, called the Shoreline Trail, would include one mile of elevated walkway on pilings in the river itself, or next to it. At least 330 pilings would be needed, by unofficial count.8

The 2020 Master Plan also introduced the $59.1 million Breakneck Bridge – far bigger and more expensive than anything proposed before. The bridge would carry pedestrians and bicyclists over the railroad tracks that separate the riverfront and Route 9D.9 The bridge, however, is controversial, as its construction would anchor the entire Fjord Trail. By its sheer size and expense, the bridge could make the rest of the Fjord Trail seem preordained – a fait accompli.

Neither Davis nor Scenic Hudson has publicly estimated the Fjord Trail’s total cost, nor broken down where the money will come from. Scenic Hudson is counting heavily on Davis donations. In recent years, a Davis family foundation has lavished riches upon Scenic Hudson and the Fjord Trail. The foundation gave $28 million to Scenic Hudson itself, and another $59.6 million for the Fjord Trail.10

According to a budget obtained by Watching the Hudson, the first segment,11 the “Breakneck Connector and Bridge,” is estimated to cost $98.5 million, being $39.4 million for the connector, and $59.1 million for the bridge.12 The budget is attached as Exhibit A.

Scenic Hudson has bundled the popular traffic and parking improvements on Route 9D (the Breakneck connector), with the disputed Breakneck bridge. You cannot get one without the other. It’s a package deal.

Fjord Trail opponents have many concerns, including the walkway’s effect on the sensitive riverfront and threatened species; the lack of assurance that the project is fully funded, both for construction and ongoing maintenance; and most especially the effect of crowds on the Village of Cold Spring, population 2,000. Scenic Hudson has estimated the Fjord Trail will draw about 600,000 visitors per year, and boasts that the Fjord Trail will be “a new signature destination in the Hudson Valley that is sure to be of state and national prominence.”13 If true, the character of the Village would be transformed. Some merchants look forward to the expected crowds, but many residents do not. Whatever their reasons for opposition, citizens may have no way to stop, or merely slow down, the Fjord Trail except a SEQRA lawsuit. They’ve never been given the chance to vote on the Fjord Trail.

FROM STORM KING TO SEGMENTATION

Scenic Hudson is one of the most-admired environmental protection groups in the country.

Founded 61 years ago as the Scenic Hudson Preservation Conference, Scenic Hudson often is credited with launching the modern environmental movement with its landmark Storm King case.14 Tiny Scenic Hudson, a fledgling citizens group led by Frances “Franny” Reese of Dutchess County, prevented mighty Con Edison from building a pumped storage hydroelectric power plant on Storm King in Cornwall. The project would have defaced the majestic mountain and killed striped bass in the river. Scenic Hudson was very much the underdog, but Mrs. Reese and her determined and sophisticated allies prevailed against Con Ed after a 17-year court battle.

Rulings from the Storm King case were incorporated in the 1969 National Environmental Policy Act, which established the Environmental Protection Agency and mandated environmental impact studies. Scenic Hudson helped secure passage of other important legislation, including the Clean Water Act of 1977 and the 1980 Superfund Law.15

The early Scenic Hudson also aggressively sued developers who would pollute, degrade or despoil the Hudson Valley. And Scenic Hudson sued developers who tried to segment their projects. For example, in 1999, Scenic Hudson brought an anti-segmentation lawsuit in Fishkill. Scenic Hudson won, and successfully protected a threatened species, the timber rattlesnake, from a gravel mining operation.16

In an eyebrow-raising twist, Scenic Hudson now is the developer, and Scenic Hudson has segmented the Fjord Trail.17 And timber rattlers are living in the lands that will be developed.18

Segmentation is explicitly contrary to the intent of SEQRA. Nevertheless, if they can get away with it, some developers will segment to evade careful environmental review of a project. They will split up a project into two or more smaller, supposedly independent, segments. That way, each segment may pass review, whereas the project as a whole might not have. “Cumulative effects” may escape scrutiny. Or sometimes developers try to segment by saying their project will proceed at different times, in different phases. Either way, “considering only a part or segment of an action is contrary to the intent of SEQR,” the law says.19

For the Breakneck Connector and Bridge, Scenic Hudson needed two related SEQRA approvals.20 One was for segmentation itself. The other approval sought was a “declaration of significance,” that building the Breakneck segment “will not result in any significant adverse environmental impacts.” That’s called a “negative declaration.”21 The “determination of significance” is “the most critical step in the SEQR process,” according to the State Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC).22

Scenic Hudson got both approvals, on December 28, 2022.23

The approvals came from the State Parks department, which has a cozy relationship with Scenic Hudson, and will benefit from the Fjord Trail.24 As the “lead agency” reviewing the application, Parks had sole discretion to issue a negative, or positive, declaration.

The negative declaration meant that Scenic Hudson didn’t have to prepare an environmental impact statement (EIS) for that segment – it could begin construction.25 A positive declaration, by contrast, would have forced an EIS, putting the project on a continuing hold. A positive declaration is for projects that “may have a significant adverse impact on the environment,” whereas a negative declaration is for projects that “will not result in any significant adverse environmental impacts.”26

Commercial developers – such as those Scenic Hudson has sued in the past – typically expect, but don’t particularly relish, the EIS process. They see it as a cost of doing business. Often, overburdened local officials are outmatched by developers who have money, expertise, and clear objectives. The developers, however, face risks. Even public officials who privately promise their support, may wobble in the face of strong community opposition. Lawsuits may be filed, which create uncertainty, run up costs, and cause delays. An EIS may lead to further mandated environmental studies. Endangered species that weren’t identified earlier, or protected habitats that weren’t previously known, may be found at or near the construction site.27 To protect known rare species, developers may be ordered to “mitigate” the environmental harm – for example, construction may be stopped during bat nesting season, or rare turtles ordered found, and relocated, before site work can begin – adjustments that can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars.

But Scenic Hudson isn’t a commercial developer, it’s an environmental protection organization, with a splendid, national reputation. You would think it would gladly prepare an environmental impact statement, and a first-rate one, too. A model for others to emulate.

Scenic Hudson didn’t want to do that. Segmentation was approved; work has begun. In March, crews cut down 179 trees28 along Route 9D, to relocate utility lines and improve the view. The main construction on the Breakneck Connector and Bridge will begin in November 2024, Scenic Hudson promises.29

Segmentation is “contrary to the intent of SEQRA” – so why did Parks allow it?

Drawing of the proposed Breakneck Bridge, looking from North to South. The bridge is shown crossing over the Metro North railroad tracks just north of the Breakneck tunnels, and skirting the NYC DEP’s Hudson River Drainage Chamber (building at top right). State Route 9D is on the left; the Hudson River is on the far right. Drawing by Scenic Hudson consultants GOA Architecture, of New Haven, CT. Other stylized drawings, and a video, are available at GOA’s website, at: https://www.goaarchitecture.com/projects/HHFT-Bridge

SCENIC HUDSON’S STRANGE ARGUMENT FOR SEGMENTATION

Scenic Hudson made a strange claim to justify its segmentation application. Scenic Hudson asserted that the Breakneck Connector and Bridge would be useful even if the rest of the Fjord Trail is never built. Standing alone, it would have “independent utility.”30

The argument may be plausible about the connector – the automobile and pedestrian safety and parking improvements along Route 9D. But not about the bridge. The bridge is useless to Scenic Hudson except as part of the Fjord Trail.

What about the prejudicial effect of erecting the $59.1 million bridge now, first, before any other part of the disputed project is approved? Neither Scenic Hudson nor Parks discussed that – or any other reason against segmentation.

There are plenty of possible legal reasons to deny segmentation. The SEQR Handbook, which is the standard reference guide, lists eight factors to test for illegal segmentation. Several, at least, are implicated by the Breakneck Connector and Bridge.31 In particular, “inducement” – does the approval of one phase or segment commit the agency to approve other phases? A $59.1 million bridge doesn’t force Parks to approve the rest of the Fjord Trail, but the pressure would be enormous.32 We cannot prove that Scenic Hudson intended coercion by getting the bridge approved first – but we haven’t heard any good reason for it, either.

We’ve reproduced what The SEQR Handbook says about segmentation, at Exhibit B.

Scenic Hudson gave two main reasons why it thought the Breakneck Connector and Bridge would be “important and essential as a stand-alone project.”33

“Safety” was the first reason. According to Scenic Hudson, “[t]he primary purpose of the Project is to address clear and present safety risks that exist at this specific location.”34

By referring to “the Project,” however, Scenic Hudson blurred the distinction between the connector and the bridge. The connector has safety features, but the bridge does not. The bridge won’t make Route 9D any safer – it won’t bring hikers east across Route 9D to the hiking trails. It will stand entirely on the west side of the highway. The bridge will cross over the Metro North railroad tracks for the Fjord Trail.

Scenic Hudson also failed to provide any documentation – which SEQRA requires – for its safety claims.35 As shown in our May 10 article, Scenic Hudson’s “safety crisis” claims for the connector are overblown, and contradicted by police reports and other public records.36 The records show that over the past 10 years, there have been no fatal auto accidents, and no auto accidents with serious injuries, along Route 9D in the Breakneck area. For that reason, the State Department of Transportation considers the roadway “safe.”

In its decision, Parks parroted, and unquestioningly accepted, Scenic Hudson’s safety claims. “The Project has independent utility to address clear and present safety risks that exist at this specific location,” Parks said.37

Parks also didn’t ask why the bridge had to be built now, immediately, before the rest of the Fjord Trail was approved.38 No “urgent safety reason” justifies the bridge.

The second segmentation rationale was novel. Even if the rest of the Fjord Trail is never built, Scenic Hudson said, the bridge would be useful – not to it, but to the New York City Department of Environmental Protection (DEP). Therefore, Scenic Hudson said, it should be allowed to build the bridge – and now.

Although the DEP isn’t proposing to build its own bridge, if Scenic Hudson builds one, the DEP wants to use it.

The DEP maintains a Catskill Aqueduct facility at Breakneck called the Hudson River Drainage Chamber. The property is landlocked, except for a footpath. The DEP would like to be able to drive its vehicles over the new bridge, to make occasional maintenance trips to the chamber.39

Obviously, Scenic Hudson intends the bridge for the Fjord Trail, not for the DEP. But, quite by coincidence, the DEP has provided Scenic Hudson with a convenient, although contrived, pretext for segmentation.

Did Parks truly believe that Scenic Hudson and Chris Davis wanted to build and pay for a bridge – standing alone with no Fjord Trail to connect to – as a gift to the DEP?40 That Scenic Hudson and Chris Davis would walk away, happily, with no Fjord Trail but a nice new bridge for the DEP?

Scenic Hudson hadn’t previously shown any concern about the DEP’s drainage chamber problems. In Scenic Hudson’s 2020 Master Plan, which is 471 pages long, the chamber doesn’t even rate a single mention!41

The DEP, however, likes the idea of a Breakneck bridge, if its employees can use it. In December 2023, the DEP agreed to pay $14 million if Scenic Hudson would upgrade the pedestrian bridge to support the light trucks that DEP employees would drive to the chamber.42

In another coincidence, the DEP is ready to begin a long-planned, $75.6 million, reconstruction of its 107-year-old drainage chamber.43 The DEP, however, isn’t waiting for the Scenic Hudson bridge, and doesn’t expect to use it, for the reconstruction project. Instead, the DEP will float two barges in the river to bring in the heavy equipment that it needs. Not even the upgraded Scenic Hudson bridge could support the heavy equipment.44

THE PARKS DEPARTMENT: CONFLICTED, AND UNABLE TO GIVE THE FJORD TRAIL A “HARD LOOK”

As lead agency, Parks has played a crucial regulatory role in reviewing the Fjord Trail. But Parks and Scenic Hudson have a close bond – not the arm’s-length relationship ordinarily required between a regulator and an applicant.

Could Parks be truly objective and impartial?

SEQRA imposes few conflict of interest rules, but does require that lead agencies take a “hard look” at SEQRA applications.45

Examples of the close relationship between Parks and Scenic Hudson include:

The Fjord Trail is a “public-private partnership” between Parks and Scenic Hudson. The Fjord Trail previously was a Parks project – in 2015, Parks was the Fjord Trail’s SEQRA applicant.46 When the project ran out of money, Scenic Hudson, funded by Davis, took over as applicant. In other words, the Fjord Trail is as much Parks’ project as Scenic Hudson’s.

Parks would benefit from the Fjord Trail, which would become part of the State parks system. Parks would own the new $59.1 million Breakneck bridge.47 Parks would enjoy the prestige of a “world-class park,” if the Fjord Trail became that.

Scenic Hudson and Parks signed a 21-page “Cooperative Agreement” on April 1, 2021, “to cooperate on the planning and development of the Fjord Trail.”48 The agreement is separate from the official SEQRA approval process. The relationships, though, are hopelessly tangled. The agreement predates by seven months Scenic Hudson’s SEQRA application for the Breakneck segment.49

In the Cooperative Agreement, Scenic Hudson and Parks agreed that Parks will be the lead agency for “ongoing and future reviews of segments of the Fjord Trail Project under SEQRA.”50 SEQRA, however, forbids an applicant from selecting its own lead agency.51

The “Responsible Officer” for Parks who signed the SEQRA approval, Linda G. Cooper, was a vocal Fjord Trail supporter long before the SEQRA process was completed. During the SEQRA review period, she and Scenic Hudson officials spoke at a public ceremony celebrating $20 million in State funds for the Breakneck segment. The Fjord Trail, she said, is “going to be amazing!”52

Scenic Hudson and Parks evidently coordinated and consulted with each other on Scenic Hudson’s SEQRA application for the Breakneck segment.53

Despite the close ties, Linda Cooper insists that Parks is independent – and running the show. “Neither [Chris Davis] nor organizations like Scenic Hudson are dictating to Parks what the Trail will be,” Cooper asserted, to a Cold Spring resident who wrote a protest letter to Governor Kathy Hochul.54

The SEQRA review of the Fjord Trail is not over. Only the one segment has been reviewed, the Breakneck Connector and Bridge. The rest of the Fjord Trail still needs SEQRA review.

There are indications that Scenic Hudson may try to “segment” again – to cut off another piece of the Fjord Trail for separate SEQRA review. Scenic Hudson has said it plans two environmental impact statements: a “generic” one for the overall trail, and a separate, segmented, one for the Shoreline Trail.55 The Shoreline Trail, the next construction “phase,” is ecologically sensitive. Scenic Hudson plans significant riverfront disturbance: as mentioned, at least 330 pilings in or alongside the Hudson River.

From left to right: Scenic Hudson President Edward “Ned” Sullivan; New York State Parks department regional director Linda G. Cooper; Cold Spring Mayor Kathleen E. Foley. Photo taken at April 21, 2022 ceremony celebrating appropriation of $20 million in State taxpayer funds for the Breakneck segment of the Fjord Trail.

SCENIC HUDSON: NOTHING TO SAY ABOUT ENDANGERED SPECIES

In its Breakneck application, Scenic Hudson listed four endangered species, seven other rare species, and two rare plants, that “may potentially occur in or near the Project Site.”56 Besides the listing, it offered no substantive discussion of the fate of these 13 rare species, at all. Scenic Hudson left that up to Parks.

The three pages, total, in which Scenic Hudson mentioned endangered and rare species on its SEQRA application are reproduced on Exhibit C.

On Parks’ decision on the application, in a check-the-box section,57 Parks checked that the project would have no impact, or only small impact, on endangered or threatened species, or species of special concern or conservation need, or their habitats.

In an attachment,58 Parks described what investigation Scenic Hudson had made into possible harm to endangered and rare species – oddly, as Scenic Hudson hadn’t provided that information in its application. Parks said that Scenic Hudson had “multiple consultation occurrences (i.e., calls, meetings, on-site visits)” with DEC personnel.

Parks also said that “consultation with [the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service] has been conducted” (by whom wasn’t stated) “through its IPaC system.” While that sounded reassuring, the “consultation” did not mean speaking to someone. The “IPaC system” is a website, free and open to the public, that lists by location Federally-recognized endangered species.59

Parks also promised that “consultation with the National Marine Fisheries Service … will be conducted during the permitting process.”

The above descriptions don’t sound like a robust investigation into the project’s possible effect on endangered and rare species. An in-depth study, however, normally would be conducted as part of an environmental impact statement – which Scenic Hudson wanted to avoid. And did avoid, once Parks gave it the negative declaration.

Scenic Hudson also needed permits from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, for disturbance to wetlands and the river – and got them without any effective review at all.60

A lone Army Corps engineer was assigned to review the project. Scenic Hudson buried him in paperwork, on a computer file. When he got the file, Brian A. Orzel was bowled over. He emailed a DEC colleague: “You weren’t kidding about that file – almost 2 GB!” The Army Corps had 45 days to respond to a “pre-construction notification,” or else the permits would be deemed granted. “Due to my excessive work load, I was unable to provide a written determination within 45 days of its submission,” Orzel wrote in an email. As a result, “the applicant may proceed with the project as proposed.”

For a summary of the endangered and rare species that may be found in the Breakneck area, and measures that Parks proposed to mitigate harm to them, see Exhibit D.61 For mitigation measures ordered by the DEC, see Exhibit E.62

PARKS’ REVIEW – AESTHETICS

If Parks had identified only one “significant adverse environmental impact” – a possible impact, that may occur – it would have had to issue a “positive declaration,” requiring an environmental impact statement.63

For a while, it was touch and go. On the SEQRA form, Parks recognized 81 possible environmental impacts at Breakneck. Then Parks checked off 80 of the 81 boxes, that “no or small impact may occur.”

But what about that one other box, which Parks checked, that a “moderate to large impact may occur?” If that couldn’t be reversed on further review, Parks would be forced to issue Scenic Hudson the positive declaration.

The problem was that Scenic Hudson’s bridge might be … ugly.

The bridge site is in the Hudson Highlands, a “Scenic Area of Statewide Significance.” Parks launched an “aesthetic” review.

Parks said that someone – it didn’t specify who – performed “a vantage point analysis” from “various viewpoints,” and made “renderings of how the Project would appear.”64

The viewpoints included from Storm King, directly across the river. In the Storm King court case, one concern was the view from East to West, looking at Storm King. Con Ed “would have blasted the northern face of the mountain,” as Scenic Hudson President Ned Sullivan has put it.65 Now, the concern was the opposite view – how would the east side of the river look, once altered by a bridge 445 feet long, 38 feet high, and 30 feet wide?66 And this, in an environmental review process that had origins in the 1965 Storm King case.

Not to worry. After three pages, Parks concluded there would be no “significant adverse visual impact.” The bridge would be “as visually quiet as possible.” It would have an attractive “curvilinear design.” It would “blend into the landscape.”

Besides, with its “minimal” profile, the bridge would be better-looking than the DEP’s “prominent” drainage chamber.

May 17, 2024

Photos above show the planned route of the Fjord Trail (in yellow) at the Breakneck area, including the new Breakneck Bridge. Top photo shows northern section of the Breakneck Connector; bottom photo shows the southern section, including the Bridge. The images can be downloaded at the link immediately below.

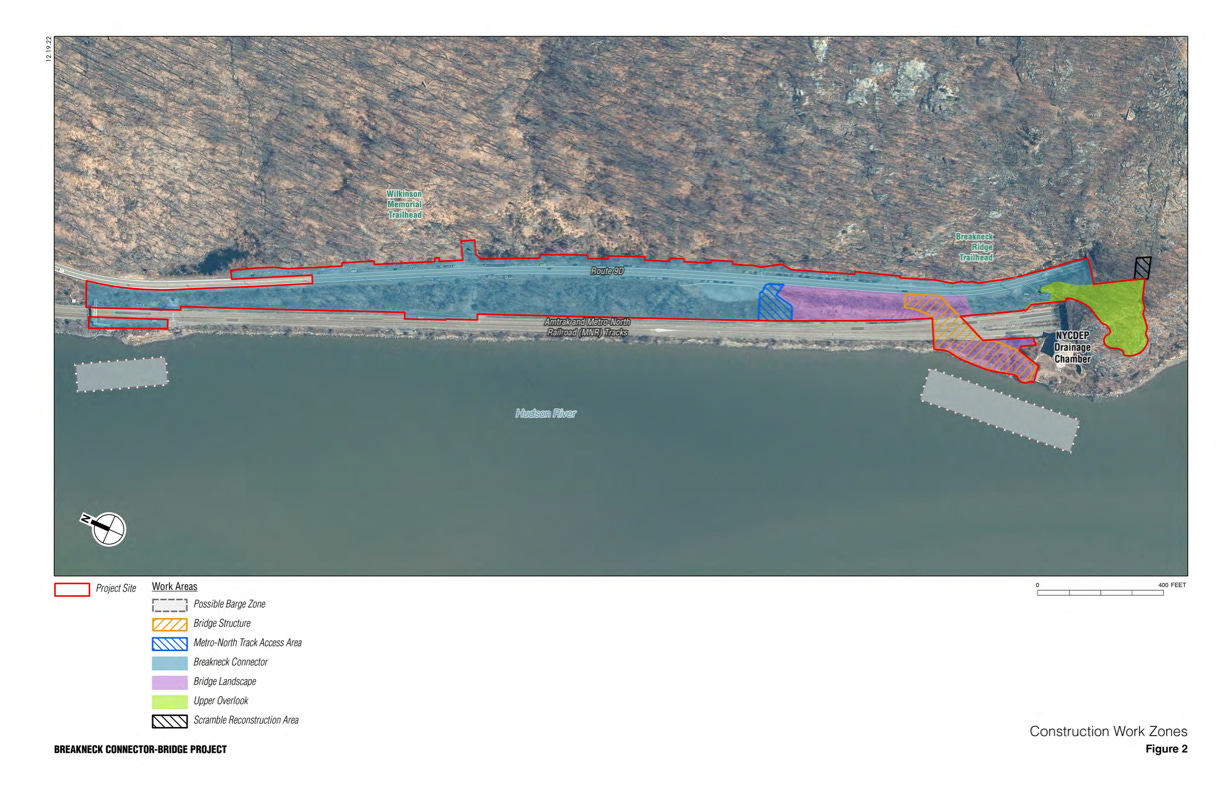

Photo, above, has overlays showing the planned work areas of the Breakneck Connector and Bridge segment of the Fjord Trail. The image can be downloaded at the link immediately below.

BELOW ARE PDF FILES THAT YOU CAN DOWNLOAD FOR (i) THE EXHIBITS TO THIS REPORT, AND (ii) THE ENTIRE REPORT, INCLUDING THE EXHIBITS.

FOOTNOTES

Many documents that are cited in this report can be found under the “Resources” tab on the website of Protect the Highlands (“PTH”), the leading anti-Fjord Trail citizens group. The library of public documents (the “PTH Documents Library”) is at: https://www.protectthehighlands.org/documents. PTH obtained many of these documents by making formal requests to State agencies using the state Freedom of Information Law (“FOIL”). Few official public documents – as opposed to videos, marketing materials, the 2020 Master Plan, and other unofficial materials not submitted under the SEQRA process – are available on the website for Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail, Inc. (“HHFT”), the Scenic Hudson wholly-owned subsidiary that is sponsoring the Fjord Trail.

The New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation, referred to in this report as the State Parks department, or “Parks.”

See the “Greenway Grant Feasibility Study” by the Town of Philipstown (Sept. 2007) (also called the “Hudson Fjord Hike/Bike Trail Capital Improvements Feasibility Study”) (available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1). The local pathway would become part of the Hudson River Valley Greenway Trail system. The pathway was planned from Little Stony Point to the Breakneck Ridge train station, or about 1.57 miles, plus a .43 mile northward extension in Fishkill.

Apparently, the concept of “connecting” hikers to hiking trails is the origin of the later-used “Breakneck Connector” name.

The 2015 Master Plan is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1. The Breakneck Connector segment – not including the bridge – was reviewed under SEQRA and received a negative declaration on March 22, 2016, meaning that no additional environmental review was necessary. At that time, the Town of Fishkill was the lead agency. When the Fjord Trail project was re-imagined under the 2020 Master Plan, a new SEQRA review for the Breakneck segment was begun, to replace and supersede the 2016 review. The new application, dated Nov. 3, 2021, was made to reflect that the Breakneck bridge had been added to the previously-approved Breakneck Connector, plus new “upgrades” to the Upper Overlook area. Parks replaced Fishkill as the lead agency, partly because, the application said (without further explanation), Parks will have ownership interests in the Breakneck Connector and Bridge lands. See Breakneck Connector and Bridge Project, Full EAF Part 1 – Attachment A” (rev. Dec. 27, 2022), at p. 6 (“Scenic Hudson FEAF Attachment A”); available at the PTH Documents Library, see supra, note 1.

See R. Kreitner, “The Battle Over the Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail,” Chronogram magazine (Oct. 27, 2023), available at https://www.chronogram.com/river-newsroom/the-battle-over-the-hudson-highlands-fjord-trail-19300194.

The 2020 Master Plan is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1. For more information about the mutual fund company, called The Davis Funds, see our article, “A Difficult Period for Chris Davis As Clients Pulled $77.6 Billion From His Funds,” at the Watching the Hudson Substack website (“Davis Client Withdrawals”), here: https://watchingthehudson.substack.com/p/a-difficult-period-for-chris-davis

Scenic Hudson hasn’t disclosed the exact number of pilings, but a minimum of 330 can be calculated by what its consultants, SCAPE architects of New York City, divulged at a public meeting on March 11, 2024. Between Dockside Park and Little Stony Point, a half-mile of trail would be elevated on pilings, and there would be 130 spans, each 20 feet long. The spans would be a “double-pile” structure, meaning at least two pilings per span, or a total of 260. From Little Stony Point to Breakneck, another half-mile of trail would be elevated on pilings, with 70 spans, each 50 feet long. These spans would be a “mono-pile” structure, meaning at least one piling per span.

The 2015 Master Plan contemplated a rudimentary and utilitarian bicycle and pedestrian bridge over the railroad tracks, containing none of the design elements of the 2020 Master Plan’s Breakneck Bridge. The cost, not estimated in the plan, presumably was a small fraction of the $59.1 million for today’s bridge. See a drawing of the 2015 bridge at the 2015 Master Plan, at page 39. The 2015 Request for Proposals (RFP) for the Breakneck Connector did not include the bridge. It had four components: (i) a half-mile bicycle-pedestrian trail from the Breakneck Ridge train station to the Breakneck Ridge trailhead, (ii) improvements to the train station, (iii) improved parking along Route 9D at Breakneck, and (iv) a new welcome area by the Breakneck parking lot. The 2015 Master Plan, and the RFP, are available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

Information is from tax filings by the Shelby Cullom Davis Charitable Fund Inc. for the years 2012 through 2022, available at the ProPublica website, here: https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/203734688/202302769349101100/full. For more information about the foundation, which was started and funded by Chris Davis’ grandfather, see Davis Client Withdrawals article, supra note 7.

The Fjord Trail is proposed to be built in five construction “phases,” with the Breakneck Connector and Bridge being the first “phase.” Scenic Hudson’s phasing for construction hopscotches oddly along the shoreline. From Breakneck (phase 1), it would go south of Breakneck (phase 2A), then north of Breakneck (phase 2B), then south again (phase 3), then north again (phase 4), and finally back to the Breakneck area (phase 5). See HHFT website at: https://hhft.org/about-the-fjord-trail/timeline/.

Previous estimates from Scenic Hudson put the Breakneck Connector and Bridge cost at $86 million. Watching the Hudson obtained the budget document at Exhibit A after filing with Parks (on Jan. 31, 2024) a FOIL request for all Fjord Trail budget records over the past five years. On Feb. 26, 2024, Parks denied the request except for one document, an undated “summary” of a “Year-One Operating Budget” (apparently for the Breakneck segment) that showed costs, but no revenues. Watching the Hudson appealed, and a Parks appeals officer on April 3, 2024 reversed and released two other budget documents, including that on Exhibit A. Apparently Parks has no budgets for the entire Fjord Trail. Because Scenic Hudson and HHFT are private entities, they are not subject to FOIL, although documents they share with public agencies may have to be disclosed under FOIL.

Quote from Scenic Hudson President Edward “Ned” Sullivan, in a Jan. 13, 2022 email to then-State Parks Commissioner Erik Kulleseid, reproduced as Exhibit F to the Overblown Safety Claims Article, infra note 36.

The Storm King case established the principle that citizens could intervene in court cases affecting the environment even if those individuals were not at risk of sustaining economic damages to their property – they had “legal standing” to sue. Scenic Hudson v. Fed. Power Comm’n, 354 F.2d 608 (2d Cir. 1965). For a description of the Storm King case, by a leading lawyer who litigated the case for 15 years, see Albert K. Butzel, Storm King Revisited: A View from the Mountaintop, 31 Pace Envtl. L. Rev. 370 (2014); see also a condensed version of the article at the Scenic Hudson website, here: https://www.scenichudson.org/news/storm-king-revisited-a-view-from-the-mountaintop/ Marist College in Poughkeepsie has an important archive of historical documents about the Scenic Hudson decision (the Marist Environmental History Project); see https://archives.marist.edu/mehp/scenicdecision.html.

W. Saxon, “Frances Reese, 85, Defender of Hudson Valley,” The New York Times (July 9, 2003) (obituary).

Scenic Hudson won the segmentation lawsuit against the Town of Fishkill, for a two-step change to its zoning rules that benefitted a gravel pit owner. In re Scenic Hudson v. Town of Fishkill, 258 A.D.2d 654 (N.Y. App. Div 1999). The court found that the Town Board had improperly segmented its review of the proposed mining operation (by first rezoning a 215-acre site, and then making a determination that mining was a permitted use there). SEQRA applies not only to construction activities, but also to public agency planning and policy-making activities, and rules and regulations. See SEQRA definition of “actions” at 6 NYCRR § 617.2(b).

Has Scenic Hudson’s mission changed, since its early days? Scenic Hudson’s mission statement today is diffuse: “Scenic Hudson preserves land and farms and creates parks that connect people with the inspirational power of the Hudson River, while fighting threats to the river and natural resources that are the foundation of the valley's prosperity. Our work is guided by our vision for the region: The Hudson Valley is a community of informed and engaged residents working to make the region a model of vibrant riverfront cities and towns linked by inviting parks and trails, beautiful and resilient landscapes, and productive farms.” See Scenic Hudson Federal income tax return on Form 990, Schedule 0, “Description of Organization’s Mission and Significant Activities” (2020), available at https://projects.propublica.org/nonprofits/organizations/132898799/202300749349301720/full

According to the Parks department’s approval of Scenic Hudson’s SEQRA application for the Breakneck segment, within 1.5 miles of the project site, timber rattlesnakes are known to hibernate, give birth, bask, shed skin, and forage. Parks staff “conducted targeted surveys” to determine the potential for timber rattlesnake habitats in the project site. Parks concluded that the Upper Outlook area in the project site has potential timber rattlesnake habitat suitable for foraging and basking, but likely unsuitable for gestating, birthing, or denning. Woodlands in the area are also “potential foraging habitat for the species.” See Breakneck Connector and Bridge Project, Full Environmental Assessment Form (FEAF) Part 3 – Attachment A, at p. 18 (Dec. 27, 2022) (decision on SEQRA application by Parks) (“Parks FEAF Attachment A”). The document is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

6 NYCRR § 617.3(g)(1). “Segmentation” is defined in SEQRA as “the division of the environmental review of an action such that various activities or stages are addressed under [SEQRA] as thought they were independent, unrelated activities, needing individual determinations of significance.” 6 NYCRR § 617.2(ah).

The application was made on Nov. 3, 2021 by Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail, Inc. (HHFT), a non-profit corporation which was incorporated in January 2020, and wholly-owned by Scenic Hudson. It was signed by HHFT Executive Director Amy Kacala. For simplicity in this report, we refer to Scenic Hudson and HHFT interchangeably. The application, and the HHFT certificate of incorporation, are available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

See the SEQRA definition of “negative declaration” at 6 NYCCRR § 617.2(z).

The SEQR Handbook, at p. 76 (emphasis added). First published in 1982, the handbook has been “a standard reference book for local government officials, environmental consultants, attorneys, permit applicants, and the public.” Id., at preface. The SEQR Handbook is available on the DEC’s website at https://extapps.dec.ny.gov/docs/permits_ej_operations_pdf/seqrhandbook.pdf.

The leading anti-Fjord Trail citizens group, Protect the Highlands, began to form around the time of the negative declaration, and had its first meeting in February 2023, according to the group’s President, Dave Merandy, a former Cold Spring Mayor. By May 2023, the group had organized a steering committee, but the time to file a legal challenge had passed. The group didn’t hire a lawyer until January 2024, when it engaged Philip H. Gitlen of Whiteman Osterman & Hanna, in Albany.

There is no centralized review agency for SEQRA applications – the DEC, for example, typically doesn’t review them. Instead, various “involved agencies” – which are public agencies that have some kind of discretionary funding or approval power over at least a part of the proposed project (for example, a Planning Board that will rule on a zone change application) – decide among themselves which one will be the “lead agency,” making the key decisions. See The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at p. 59.

Once Parks made the negative declaration, other government agencies that had discretionary authority over the project (so-called “involved agencies”) became free to make their final decisions on the action (their decision-making had been held in abeyance during the SEQRA review). See The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at p. 63. After the negative declaration, the Breakneck Connector and Bridge project received permits from the DEC (to excavate and fill in navigable waters, and stream disturbance), with conditions, on Dec. 19, 2023 – attached as Exhibit E; from the NYS Department of State (for consistency with the NYS Coastal Management Program), with modifications, on Oct. 6, 2023; and from the Army Corps of Engineers (Nationwide General Permit), by non-action by the Corps of Engineers within the prescribed 45-day period after the April 5, 2023 submission of the pre-construction notification. The DEC and Department of State permits are available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

Emphasis added. “Negative declaration” is defined under SEQRA at 6 NYCCRR § 617.2(z) and “positive declaration” is defined at 6 NYCCRR § 617.2(ad). For projects like the Fjord Trail, SEQRA requires a preliminary environmental review (EAF, or Environmental Assessment Form), leading either to a “negative” or “positive” declaration.

For example, Scenic Hudson didn’t list a rare plant, the small whorled pogonia, a perennial member of the orchid family, on its SEQRA application for the Breakneck segment – but the pogonia was identified as a “threatened” species on the Federal list, and a “protected” species on the New York State list, in the AECOM Report for the Hudson River Drainage Chamber. See the AECOM Report, infra note 43, at 64th (unnumbered) page. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says of the small whorled pogonia, under the heading “Endangered Species:” “[t]his orchid is one of the rarest in the United States.” See https://www.epa.gov/endangered-species/endangered-species-save-our-species-information-small-whorled-pogonia#:~:text=This%20orchid%20is%20one%20of,forests%20were%20cleared%20for%20development

M. Ferris, “Hudson Highlands Fjord Trail Still Divides Opinion After Changes,” Albany Times Union (April 8, 2024), at https://www.timesunion.com/hudsonvalley/outdoors/article/fjord-trail-hudson-highlands-changes-controversy-19387491.php

See “Central Hudson To Begin Utility Pole Relocation Work,” press release from HHFT (Jan. 24, 2024).

“[E]ven if nothing else were ever constructed for the larger Fjord Trail either north or south of the Project, this section comprising the Breakneck Connector and Bridge is important and essential as a stand-alone project.” Scenic Hudson FEAF Attachment A, supra note 5, at pp. 11-12.

See the discussion of segmentation in The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at pp. 53-55, attached as Exhibit B.

The “sunk cost fallacy,” however, says that it is a mistake to throw good money after bad.

Other reasons Scenic Hudson gave to defend segmentation included: (i) regarding timing, the “urgent need” to address “pedestrian safety and congestion issues” along Route 9D, (ii) that the planning and design of the Breakneck segment have “progressed much farther towards completion” than that for the rest of the Fjord Trail, (iii) that funding is available “or in the final stages of negotiation” for the Breakneck segment, “whereas the funding for the Fjord Trail is not determined or fully available at this time,” (iv) the Fjord Trail’s construction timeline is “speculative,” and (iv) Parks either owns or is in the process of acquiring the project site (except for the train station), whereas Parks had not yet acquired the real property interests it needs for the rest of the Fjord Trail, and a “protracted negotiation process” might be required. Scenic Hudson FEAF Attachment A, supra note 5, at pp. 11-12.

Id., at p. 11.

“The decision to segment a review must be supported by documentation that justifies the decision, and must demonstrate that such a review will be no less protective of the environment.” The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at p. 54.

See M. Stillman & P. Weiss, “How Scenic Hudson’s Overblown ‘Safety Crisis’ Claims Got the Fjord Trail $20 Million in Taxpayer Funds” (May 10, 2024) (“Overblown Safety Claims Article”), at the Watching the Hudson Substack website, at: https://watchingthehudson.substack.com/p/how-scenic-hudsons-overblown-safety?r=nonwx.

See Parks FEAF Attachment A, supra note 18, at pg. 1.

The 2020 Master Plan also failed to distinguish between the connector and the bridge regarding safety. It said that the Breakneck Connector and Bridge was proposed to be built first “due to the high volume of use and existing safety concerns of this area.” 2020 Master Plan, at pg. 459.

For example, the DEP conducts twice-a-year valve testing at the chamber. For many years, DEP employees have parked their cars off Route 9D and walked the short distance over the Breakneck railroad tunnel to the chamber. They follow the same general path over the tunnel as hikers on the Breakneck Ridge Trail. Vehicle access to the chamber was lost after Route 9D was built in 1932 and the Beacon-Cold Spring Road was abandoned. New York City has sought at-grade railroad crossings to get to the chamber, but the MTA and predecessor railroad companies have refused, for safety reasons. The chamber is the only access point for the Catskill Aqueduct’s tunnel under the Hudson River, and was completed in 1917.

The Davis foundation is expected to donate $25,160,000 for the bridge (plus $38,288,000 for the connector). See the budget at Exhibit A. One wonders what Chris Davis’ grandfather, the legendary investor Shelby Cullom Davis, would have thought about his foundation’s spending $25,160,000 as a gift to the New York City DEP. The grandfather’s frugality is well-documented in The Davis Dynasty: Fifty Years of Successful Investing on Wall Street, by John Rothchild (2003). When Chris as a young man asked his grandfather for $1 to buy a hot dog from a street cart vendor, he got a lecture on the opportunity cost of the $1 expense. Davis Dynasty, at p. 237.

In the 2020 Master Plan, the drainage chamber shows up only as a landmark on photos or maps of the site, for example on page 26. It is mis-identified as “NYC DEP Pump Station” on the map at page 39. The Catskill Aqueduct water tunnel under the Hudson is a siphon and requires no pumps. The 2020 Master Plan is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

See Agreement dated Dec. 8, 2023 between DEP and Parks (for the construction of a dual-function bridge to the Hudson River drainage chamber) (“Bridge Construction Agreement”), at p. 11. The agreement is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

A public notice for the project was published in the New York State Register on Nov. 8, 2023 (seehttps://dos.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2023/11/110823.pdf at pp. 82-83). The project is eight years late “due to budgetary constraints,” and $73.6 million over budget. The DEP already has spent $17.8 million of the $75.6 million. See details for the “CAT-399” project at the NYC Databook, at https://databook.wegov.nyc/p/CAT-399_ca-hudson-river-drainage-chamber. A global infrastructure consulting firm, AECOM, has drawn up plans. See the AECOM Permit Information Packet, Appendix C, at: https://dos.ny.gov/system/files/documents/2023/11/f-2023-0669figures.pdf (“AECOM Report”).

Scenic Hudson President Edward “Ned” Sullivan has incorrectly stated, to Governor Hochul’s top aide, Deputy Secretary Edgar Santana (now Executive Deputy Secretary), that the Breakneck bridge is essential to the DEP’s drainage chamber project. In an email on March 17, 2022, Sullivan wrote that “[t]he bridge would … provide vehicular access to a NYCDEP facility …. DEP … must have vehicular access for its construction project.” (Emphasis added; see email at Exhibit F.) In fact, the DEP isn’t planning on any vehicular access for the project. A report by DEP’s construction consultants said that “[d]irect road access to the site for heavy equipment is impossible as the site is bordered by active rail lines and is situated between the river and steep rocky terrain. Site access would be realized through the temporary placement of a flat deck barge … [and] a crane barge.” AECOM Report, pg. 59. Sullivan made his incorrect statement as part of his lobbying efforts to get $20 million in State taxpayer funds for the Fjord Trail. After the $75.6 million reconstruction is completed, how much maintenance will the chamber need – how often will DEP employees need to drive over the new bridge? Would such access really be worth $14 million to the DEP? We didn’t get an answer to that from the DEP.

See the “hard look” standard as set forth in H.O.M.E.S. v. N.Y.S. Urban Dev. Corp., 418 N.Y.S.2d 827, 69 A.D.2d 222, 232 (N.Y. App. Div. 1979). Describing the case, The SEQR Handbook said “[t]he Court held that for a negative declaration to be upheld, the record must show that the agency identified relevant areas of environmental concern, thoroughly analyzed them for significant adverse impact, and supported its determination with reasoned elaboration… The H.O.M.E.S. case established the ‘hard look’ test that is used by the courts to evaluate whether an agency’s SEQR determination should be sustained and that was subsequently incorporated into the SEQR regulations.” The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at p. 201.

Parks was both the applicant and the lead agency – a conflict that’s mind-boggling except, apparently, in SEQRA world. In October 2015, Parks issued a “positive declaration” on its own application to adopt the 2015 Master Plan. As lead agency, Parks ruled that the action “may have a significant impact on the environment.” At that time, Rose Harvey was Parks Commissioner. Erik Kulleseid was Commissioner from 2019 to 2024, leaving to become Executive Director of the Open Space Institute. The acting Commissioner today is Randy Simons. The “positive declaration” is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1. A SEQRA applicant is the same thing as a SEQRA sponsor.

Bridge Construction Agreement, supra note 42, at p. 11 (“[t]he Project shall be owned and maintained by [Parks] or another governmental entity in such condition to allow use by DEP for a period of at least 40 years”). The agreement also says that Parks “shall be the contracting entity for the Project” (id., at p. 4), and that “[t]he services to be completed by [Parks] pursuant to this Agreement shall include the construction of the Bridge,” id. at pp. 2-3.

Cooperative Agreement dated April 1, 2021 between Parks and HHFT (“Cooperative Agreement”). In the agreement, HHFT (the Scenic Hudson subsidiary) stated that “there is no actual or potential conflict of interest” that could prevent its “satisfactory and ethical performance of its obligations” under the agreement. Id., at p. 19. The agreement is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1. Scenic Hudson and Parks have collaborated on other projects, such as the 500-plus-acre Sojourner Truth State Park in Kingston.

SEQRA doesn’t explicitly allow “cooperative agreements” between an applicant and a lead agency. While under SEQRA, “agencies are strongly encouraged to enter into cooperative agreements with other agencies regularly involved in carrying out or approving the same actions for the purposes of coordinating their procedures,” Scenic Hudson is not an “agency” (nor is HHFT); see infra at note 51.

Cooperative Agreement, supra note 48, at p. 7.

The SEQR Handbook says that an applicant cannot select the lead agency. “Lead agency can only be established by agreement of the involved agencies or, in case of disagreement, through designation by the Commissioner of DEC.” The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at p. 60. HHFT is not an “agency” and so is not an “involved agency.” “Agency” is defined as “a State or local agency,” 6 NYCCRR § 617.2(c). An “involved agency” is defined as “an agency that has jurisdiction by law to fund, approve or directly undertake an action,” and includes the lead agency. 6 NYCCRR § 617.2(t).

See Overblown Safety Claims Article, supra note 36. Cooper is one of 11 Parks regional directors (Taconic region). Her comment was made at the April 21, 2022 ceremony.

The coordination between Scenic Hudson and Parks is evident from the documents themselves. The Scenic Hudson application and the Parks approval have the same date (Dec. 27, 2022), and one refers to the other – for example, the Parks approval refers the reader to the Scenic Hudson application (of the same date) for more information about why segmentation is permissible. They seem to have split up the discussion: Scenic Hudson (but not Parks) wrote about segmentation in depth, and Parks (but not Scenic Hudson) wrote about endangered species in depth. Also, Parks in its approval describes what research Scenic Hudson did on endangered species, information that isn’t in Scenic Hudson’s application.

Letter from Linda G. Cooper to Hope Scott Rogers dated June 6, 2023. To criticism that the Fjord Trail process has been secretive, Cooper replied that “this has not been and will not become a secretive process; it is just in a planning stage.”

See the discussion of the Shoreline Trail, supra note 8. Scenic Hudson made the statement that it will try to segment the Shoreline Trail in its Nov. 3, 2021 SEQRA application for the Breakneck Connector and Bridge. Scenic Hudson said that “the proposed Fjord Trail is currently undergoing a master plan and environmental review process that will take the form of a Generic Environmental Impact Statement (GEIS) for the overall trail and an Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) for the Shoreline Trail segment that is south of the proposed Breakneck Bridge.” Scenic Hudson FEAF Attachment A, supra note 5, at p. 10.

The information came from the New York Natural Heritage Program database, and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Official Species List.

Breakneck Connector and Bridge Project, Full Environmental Assessment Form (FEAF) Part 2, at p. 4 (decision on SEQRA application by Parks). The document is available at the PTH Documents Library, supra note 1.

Parks FEAF Attachment A, supra note 18, at p. 15.

“IPaC” stands for Information for Planning and Consultation. The website is at: https://ipac.ecosphere.fws.gov/

The Clean Water Act prohibits the unauthorized discharge of dredged or fill material into wetlands or rivers, 33 U.S.C. § 1251 et seq. The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 prohibits the unauthorized obstruction or alteration of the nation’s navigable waters, 33 U.S.C. § 401 et seq.

Because Scenic Hudson didn’t say anything about endangered and rare species in its application, other than list them in a table, it didn’t explicitly commit to take any of the mitigation measures identified by Parks in its decision – although it would have to comply with the conditions imposed by the DEC in the DEC permit reproduced on Exhibit E; also see note 25. Parks’ mitigation measures also raise the question whether they were conditions to the approval (the negative declaration), which can be illegal under SEQRA. “[A] lead agency clearly may not issue a negative declaration on the basis of conditions contained in the declaration itself,” said New York’s highest court in In re Merson v. McNally, 90 N.Y.2d 742, 753 (1997). “The environmental review process was not meant to be a bilateral negotiation between a developer and lead agency but, rather, an open process that also involves other interested agencies and the public,” the Court of Appeals said. Id.

See note 25 for a description of the permitting process and the DEC permit.

The SEQR Handbook, supra note 22, at p. 76: “If the lead agency finds one or more significant adverse environmental impacts, it must prepare a positive declaration identifying the significant adverse impact(s) and requiring the preparation of an Environmental Impact Statement.”

Since Linda Cooper signed the SEQRA approval on behalf of Parks as lead agency, she would have the final determination about aesthetics, and everything else in the Scenic Hudson application.

Sullivan’s comments were made at an April 21, 2022 ceremony celebrating the appropriation of $20 million in State taxpayer funds for the Breakneck segment of the Fjord Trail. A video of the ceremony is at https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=1162944597840598.

Bridge dimensions set forth at Scenic Hudson FEAF Attachment A, supra note 5, at p. 16.

It amazing how scenic Hudson just does what they want and can’t be stoped they are the biggest liars out there. Will stop at nothing for this stupid trail . Money well wasted . To accommodate tourist that do t contribute nothing but garbage to our small city and towns . These people are rude park where they think they own it. And the scenic Hudson I remember with the quarry and rattle snakes . Wow but they will destroy a lot more to get what they want but that’s ok we are scenic Hudson . Most evil group on earth .